|

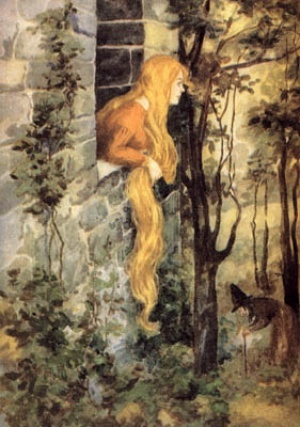

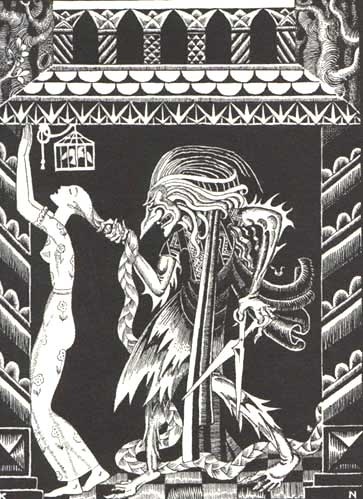

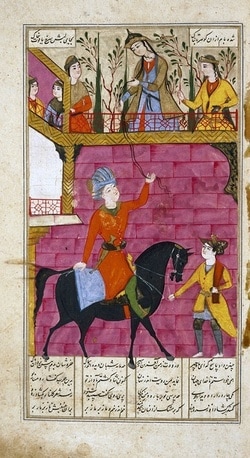

Seeking Rapunzel by Chris Fitzner (@chrisfitzner) “Rapunzel” is a deceptively simple tale; even the name of the title character is obviously German, which would make sense seeing as it was first introduced to the world at large by the Brothers Grimm. But as I dug into the soil and began to pull at the roots of the story, I found that they ran much deeper than I had suspected. It is a story with which most of us are familiar. A husband, desperate to appease his ailing wife, gets caught stealing the lettuce she craves so desperately. The price for the theft is their long awaited child and the witch whisks the baby girl away, eventually shutting her in a tower that has neither a door nor stairs, to keep her safe from the world. Rapunzel grows up beautiful, with golden hair the witch climbs up in order to visit the tower. But the witch cannot keep the world out forever; eventually a prince discovers Rapunzel, drawn by her enchanting singing. He figures out the trick to gaining access to the tower and begins visiting after the witch is gone and the two fall in love. The witch discovers them and banishes Rapunzel far away to fend for herself and springs a trap for the prince, who falls from the tower and blinds himself on the brambles. After a time of wandering, Rapunzel and the prince are reunited, her loving tears restoring his sight. Happily ever after, right? This story makes me think twice about crossing an old crone at the salad bar. The tale that we know as “Rapunzel” came to us from the Children’s and Household Tales collection, first published by the Grimm brothers in 1812. Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm collected oral folk tales and wrote them down, sometimes editing them over time and removing the more cruel or sexual elements in some of the stories. However, their “Rapunzel” bears a strong resemblance to a French story titled “Persinette”, written by an aristocrat, Charlotte-Rose de Caumont de la Force and published in 1698. This version with its title character, Persinette (parsley), is almost identical to the Grimm’s version save for having a more detailed ending with Persinette and her lover suffering even more than Rapunzel and the prince before their eventual reunion. But if “Rapunzel” was French, how did Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm come across it as an oral folktale? They have J.C. F. Schulz to thank for that, as his translation of “Persinette” is thought to be the indirect source of “Rapunzel”. Schulz also changed the heroine’s name to Rapunzel. The Grimm brothers, however, were unaware of the stories of Schulz and Madame de la Force and assumed that the story was oral in its origin. Several similarities to Schulz’s translation may imply that at least one of the Grimm’s human sources had heard the Schulz telling. The intermixing of cultures and versions were common with folktales and took place frequently until the printed versions of the Grimm Brothers and Perrault were introduced. The trail doesn’t quite end (or begin, rather) in France with Madame de la Force either. The first literary traces of “Rapunzel” can be found in 1637, in Giambattista Basile’s Pentamerone in the story “Petrosinella” (which, derived from petrosine, again, means parsley). In Basile’s version, the lovers elope rather than suffer at the witch’s hands before a reunion. It may be that the ending we know best could have been simply the artistic licence of Madame de la Force and a craving for tragedy on the part of her readership. Flavours of the later “Rapunzel” do seem to carry Mediterranean undertones, though the name of the heroine may change from tradition to tradition. In some cultures, the witches are cannibalistic. The original folktales often involved the heroine and the prince fleeing the tower rather than succumb to the punishment that would result upon discovery. In these variants, the witches pursue the lovers but are outwitted three times (the girl often using magic that the witch taught her, no less). On the third obstacle, the witches in these tales are rendered harmless or killed, and the lovers are free. The two most memorable components in “Rapunzel”, for me at least, are the tower and the heroine’s long hair. In the versions that I have come across in my life, the witch locks Rapunzel away around age twelve to keep her safe from the world which seems to say that as the elder, she obviously knows what’s best and her child does not. The “maiden in the tower” trope can be found littered throughout old stories and “Rapunzel” holds similarities to the Tenth Century Persian tale of Rudaba, in the epic poem Shahnameh by Ferdawsi (circa 1010 CE); in it, Rudaba offers to let down her hair so that her lover, Zal, may climb up to her. We also find the tower trope in Saint Barbara, who lived sometime in the Mid-Third Century. Saint Barbara’s father locked her in a tower to preserve her from the world. During her imprisonment, she converts to Christianity from the pagan beliefs of her birth. The message of the tower and its representation of tradition, authority, and power rings loud and clear. As Mother Gothel sang in Tangled: Mother knows best. Tangled is perhaps the best known adaptation of “Rapunzel” at present and my favourite to date. It is a very loose adaptation from the Grimm’s telling to be sure. Plucky Rapunzel leaves the tower against her “mother’s” wishes in order to achieve her dream of seeing the lights, armed with only an iron skillet, a mile of magical hair, and her incredibly positive attitude. Compared to the rather flat character in the folklore, this plucky princess seems like a huge departure, or is it? The plucky lovers escaping from the witch in the Mediterranean tales seem more on level with Disney’s princess than the Grimm’s, even with all of the liberties the Disney company took with the story.  Charming (Josh Dallas) and Rapunzel (Alexandra Metz). ABC, 2014 Charming (Josh Dallas) and Rapunzel (Alexandra Metz). ABC, 2014 Once Upon a Time’s very own is slated to appear in Episode Fourteen, “The Tower”. Portrayed by Alexandra Metz, Once has already broken any and all pre-established notions of how this character should look. Will they spin straw into gold with her character as well? Will we have a new member in their ranks of plucky princesses or will she be doomed to be another footnote in the greater story arc? We will have to wait and see.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

OriginsExplore the Arthurian legend surrounding Lancelot, take a trip into the woods to discover the mythology behind Red Riding Hood or learn more about a modern day hero called Snow White. Origins provides unique insights and perspectives from talented writers into the characters we know and love, going far beyond the boundaries of Storybrooke. Archives

August 2016

Categories

All

|