|

The Miller’s Daughter

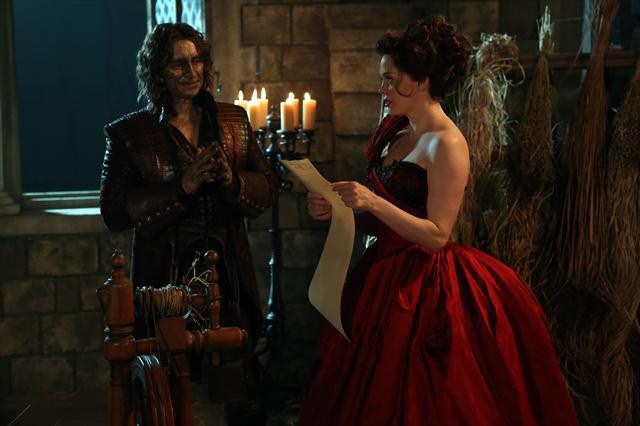

by Teresa Martin--@Teresa__Martin “The Miller’s Daughter” episode intrigued me immediately when the news of its airing reached the internet, not because of the plot, not because of “what really happened with Cora and Rumplestiltskin,” but rather in the title itself. The Once Upon A Time audience was going to be treated, for the first time in Season Two, to a classic fairy tale with the Once twist. All had seen Rumpelstiltskin and the miller’s daughter, Cora, but never seen them featured together using the source material. We had not seen the fairy tale that epitomizes one of the most popular characters on the show, Rumplestiltskin. He and the lowly daughter were finally going to be together, acting out the conflict, battle of wills, and their final estrangement. No wonder fans were salivating. The original tale, as recorded by the Grimm Brothers, presents the narrative of an unfortunate daughter whose father brags that she can spin straw into gold. When word reaches the king, she is locked in a tower to spin the gold or die in the morning. Rumplestiltskin then appears, offering to complete the task in exchange for certain items. Three successive times he does this, and the king marries her. Yet to her horror, she finds that Rumplestiltskin intends to take her first-born as payment. Seeing her distress, Rumplestiltskin takes pity on her and says that she can keep the child if she guesses his name. Sending a servant to assist her, she finds out the name, and when she says “Rumplestiltskin,” he tears himself in two falling into hell. Maria Tatar notes that while Rumplestiltskin is an imp, and portrayed as a treacherous creature, he nevertheless shows a remarkable pity for the daughter, especially in the face of her despair at losing her child. Like the Rumplestiltskin of Once Upon a Time, there is more behind the evil persona.

0 Comments

By Lori J. Fitzgerald

The Charmings may be growing magic beans to return to the Enchanted Forest, but in Episode 2x19 “Lacey,” Once Upon a Time takes us into the medieval literary setting of Sherwood Forest. Although the famous outlaw of this greenwood, Robin Hood, makes but a short appearance, his presence still gives us a glimpse of the swashbuckling legendary character and holds its weight worth in gold by advancing the symbolism and theme of this episode. Robin Hood was a character of medieval ballads which were told or sung by wandering minstrels. In a time where only members of the nobility or clergy could read, the ballads were meant as performance literature for both the commoners and the court; therefore, as in many folktales of the oral tradition, the Robin Hood stories were a constant re-creation, continually adapted and changed by the minstrels who performed them, rather than a careful, exact recitation (Bolton 348-349). Thus many of the original stories that have survived about Robin Hood and his band of outlaws are conflicting or fragmented. Medieval stories achieved some consistency once they were scribed by monks or printed, but being written down was usually the last thing that happened to a ballad. The Gest of Robyn Hode, which is a collection of these ballads, was probably first set to type by the famous medieval printer, Wynkyn de Worde (the successor to William Caxton’s printing press) around 1500, although the ballads were popular entertainment for more than a century before this. The Gest as we have it today in Middle English was compiled from a series of Gest manuscripts and printed in the collection The English and Scottish Popular Ballads by Francis James Child in the late 1800s. The Three Queens Eva, Snow, and Emma’s parallels with Traditional Christian Narrative by Teresa Martin--@Teresa__Martin Fans were thrilled when it was announced that an episode of Once Upon A Time would feature Snow’s mother. This opened up an entirely new character to explore. Of one thing I was certain, since Snow White’s mother had been established as dead it was likely that she would not be represented with the apple as her symbol. That is usually the provenance of the evil step-mother. I felt that I could put away my notes on the apple for a while. There is nothing I have against that rich symbol but I’ve already explored this theme so often that I was concerned my “Apple and Eve” symbolism was getting a little redundant. I’m surprised I have not gained the nickname “Crazy Apple Lady,” or even “Defendrix Mali.” Many possible scenarios went through my mind about how I may approach this new character and her famous daughter. I was determined that the only reason I would use the famous Garden of Eden story in this essay is if the writers went ahead and plain named the character “Eve.” A few weeks later a press release hit the web for “The Queen is Dead.” Oh. So how about those apples? Back to the Garden of Eden we go! This myth describes the great fall of humanity and locks into Snow’s mother from her name to the color of her dress. The apple is the Forbidden Fruit, a symbol of knowledge and original innocence that Adam and Eve rejected when they chose to listen to the devil, symbolized by a serpent, and ate the fruit which represents the choosing of good over evil. Eating the apple, one could say, is analogous with “crossing the line,” the act from which no person may return, so prevalent in fairy tales. However, watching the episode “The Queen is Dead” it quickly became clear that this Eva is far from the stereotypical Eve, seductress and tempter of man. Rather from her words, to their tone, and the gentle musical score, Eva is an ethereal character, almost too good to be true, giving sage advice to her daughter and accepting painful death with an astonishing peace. A week later, in “The Miller’s Daughter,” the audience learned that Eva was not kind or empathetic in her younger years. Rather she was a woman of pride who was so petty and cruel that she went out of her way to humiliate Cora, a peasant, purely for amusement. Yet this superior attitude did not last long. Young Eva is disgraced when this same peasant wins the favor of the king for spinning gold and then endures the shame of having her intended propose to another woman in front of her. Not shown onscreen, but likely to have occurred, was Eva being packed off and sent home to her kingdom as a princess who was jilted over a peasant, an object of ridicule even. Likely, given her later persona, instead of turning to bitterness and revenge, Eva chose the better path, transforming her ways such that the woman we see in “The Queen Is Dead” is the New Eva, redeemed.

|

OriginsExplore the Arthurian legend surrounding Lancelot, take a trip into the woods to discover the mythology behind Red Riding Hood or learn more about a modern day hero called Snow White. Origins provides unique insights and perspectives from talented writers into the characters we know and love, going far beyond the boundaries of Storybrooke. Archives

August 2016

Categories

All

|