Rumplestiltskin's Transformation in Once Upon a Time: Literary Anti-Hero to Hero Archetype14/1/2014 Rumplestiltskin's Transformation in Once Upon a Time: Literary Anti-Hero to Hero Archetype by Lori J. Fitzgerald (@MedievalLit) and Teresa Martin (@Teresa__Martin) “Ah, but I’m a villain. And villains don’t get happy endings.”

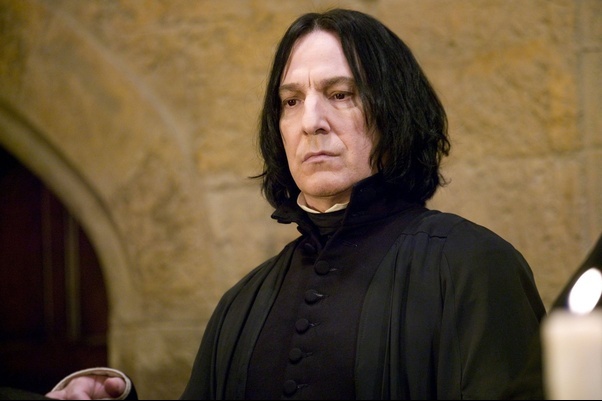

~Rumplestiltskin to his father in Episode 3x11, “Going Home” In the first few episodes of Season One on Once Upon a Time, it was easy to classify the characters into stereotypical roles: Snow White, Prince Charming, and Emma as the heroes/protagonists and the Evil Queen and Rumplestiltskin as the villains/antagonists. However, as the stories unfolded and we learned more during the Enchanted Forest flashbacks, it became apparent that the lines of good and evil were not as clear cut as they were drawn in the original fairy tales or the Disney movie versions. The creators of the show, Adam Horowitz and Eddy Kitsis, emphasized from the very beginning that their take on the characters was not a traditional one; all their creations were complex and dynamic, or changing characters with both virtues and flaws. So the Evil Queen’s revenge stems from the murder of her true love, Rumplestiltskin was betrayed by his wife and lost his son, Snow White casts a curse that kills Regina’s mother and blackens her own heart, and Emma sanctions a Lost Boy’s heart being ripped from his chest to facilitate contacting Henry. These are just some examples of “Fair is foul, and foul is fair,” as the witches in Shakespeare’s Macbeth would chant (I.i.10). So far, none of the major series players in Once Upon a Time are true villains or true heroes. They are all flawed protagonists. Rumplestiltskin in particular is a literary anti-hero, which is a flawed protagonist, or main character, which has qualities usually belonging to a villain, but these traits are tempered with other human, identifiable, and sometimes even noble traits as well. One of the earliest uses of the narrative role of anti-hero is by John Milton in Paradise Lost (1667), who casts Lucifer as the central figure in the first part of his epic poem. Lucifer is overwhelmingly arrogant, powerful, cunning and deceptive, but he is also the most beautiful angel and so charismatic that he is able to rally the other angels in his army after a crushing defeat in the war. During the Romantic period of literature (approximately 1800-1850), the anti-hero was given further “dark” qualities of being emotionally conflicted, brooding, and self-destructive by the poet Lord Byron, and thus the terms anti-hero and Byronic hero became intertwined. A Byronic hero was described by the Romantic literary critic Lord Macaulay (1800-1859) as "a man proud, moody, cynical, with defiance on his brow, and misery in his heart, a scorner of his kind, implacable in revenge, yet capable of deep and strong affection.” Byron’s pirate anti-hero in “The Corsair” (1814) is That man of loneliness and mystery, Scarce seen to smile, and seldom heard to sigh— (I, VIII) And He knew himself a villain—but he deem'd The rest no better than the thing he seem'd; And scorn'd the best as hypocrites who hid Those deeds the bolder spirit plainly did. He knew himself detested, but he knew The hearts that loath'd him, crouch'd and dreaded too. Lone, wild, and strange, he stood alike exempt From all affection and from all contempt: (I, XII) Some well-known Byronic/anti-heroes in literature include the wild and vengeful Heathcliff from Wuthering Heights by Emily Bronte and the secretive, brooding Edward Rochester from Jane Eyre by Charlotte Bronte. Both of these characters may have been patterned after Lord Byron himself, whose own lover characterized him as “mad, bad, and dangerous to know.” Severus Snape in the Harry Potter series is a well-known contemporary Byronic hero, and Anakin Skywalker/Darth Vader can also fit this role.

0 Comments

The Miller’s Daughter

by Teresa Martin--@Teresa__Martin “The Miller’s Daughter” episode intrigued me immediately when the news of its airing reached the internet, not because of the plot, not because of “what really happened with Cora and Rumplestiltskin,” but rather in the title itself. The Once Upon A Time audience was going to be treated, for the first time in Season Two, to a classic fairy tale with the Once twist. All had seen Rumpelstiltskin and the miller’s daughter, Cora, but never seen them featured together using the source material. We had not seen the fairy tale that epitomizes one of the most popular characters on the show, Rumplestiltskin. He and the lowly daughter were finally going to be together, acting out the conflict, battle of wills, and their final estrangement. No wonder fans were salivating. The original tale, as recorded by the Grimm Brothers, presents the narrative of an unfortunate daughter whose father brags that she can spin straw into gold. When word reaches the king, she is locked in a tower to spin the gold or die in the morning. Rumplestiltskin then appears, offering to complete the task in exchange for certain items. Three successive times he does this, and the king marries her. Yet to her horror, she finds that Rumplestiltskin intends to take her first-born as payment. Seeing her distress, Rumplestiltskin takes pity on her and says that she can keep the child if she guesses his name. Sending a servant to assist her, she finds out the name, and when she says “Rumplestiltskin,” he tears himself in two falling into hell. Maria Tatar notes that while Rumplestiltskin is an imp, and portrayed as a treacherous creature, he nevertheless shows a remarkable pity for the daughter, especially in the face of her despair at losing her child. Like the Rumplestiltskin of Once Upon a Time, there is more behind the evil persona.  By Amy Hood - @amylia403 Fate versus free will. It’s an argument as old as the most ancient storybooks. Can people change or escape their fate? This is a scenario we have seen repeated in Once Upon A Time. Characters that are “born” to do something, whose destinies and fates were told years before…could they change it? Was there any way they could have avoided who and what they were destined to be? The first and oldest example of a character fated to have a certain destiny is Rumplestiltskin. When we see him early in his life, he has a lovely wife, a home and dreams of starting a family. He is called to fight in the Ogre Wars, where he meets a seer. The Seer tells him that his actions the following day would cause his son to grow up without a father. Rumple assumes she means he will die, so he wounds himself in order to be sent home. This act ends up being the catalyst for future events. Milah no longer wants to be with him because he is a coward. She leaves him, pushing him to total desperation to keep the one person he has left: his son. All of these events play like dominos, one leading to the other, and ultimately lead to Rumple’s son being lost and growing up without his father, just as the Seer foretold. Beauty by Teresa Martin--@Teresa__Martin One of the most familiar expressions about beauty is that it is “more than skin deep.” This refers to the belief that it is the soul which determines whether a person is truly beautiful. However, there is great deal of difficulty in expressing this notion since the nature of beauty is often subjective. Yet there has been a gift to the world which explores and explains this attribute better than any other love story has: that of “Beauty and the Beast.” This story succeeds because the tale’s protagonist is arguably the greatest character in fairy tale fiction, and also the very namesake of this quality. Modern audiences outside of France are more apt to use her French name, Belle, due to Disney’s 1991 cartoon. This story is able to provoke strong emotional reactions because it succeeds in uniting two very seemingly different characters in a convincing manner since neither Belle nor the Beast is perfect and, as they get to know each other, they journey together through a transformative process which leads to true love. This is symbolized by the persistent symbol of resurrection through the use of light and a rose. While there are many versions of this story, three particularly illustrate these symbols and themes: the original French story, the classic Disney cartoon, and the Once Upon a Time episode “Skin Deep.” The last incarnation is worthy of note since it explicitly recognizes the theme of the story by its title, and in doing so, ingeniously takes a twist on its definition. All three however, though written years apart and for different audiences, utilize the key symbols to show that the process of transformation is wrought with sorrow and pain, but also yields the inexplicable ecstasy of true love. The first major written version of “Beauty and the Beast” was authored by Madame de Villeneuve in 1740 and published in a ladies magazine. Villeneuve presents a fascinating portrait of Belle as a character. She is the youngest daughter of a wealthy merchant with six brothers and five sisters. When her father’s business fails due to misfortune, the family is uprooted and forced to live as peasants in the countryside, performing the grueling work that accompanies this lifestyle. After the move, Belle is introduced into the story. She too experienced the disappointment of losing their comfortable lifestyle, but in contrast to her sisters who remained bitter and spiteful, Belle responded with “perseverance . . . .“firmness,” and a “strength of mind beyond her years . . . . [she] made up her mind to the position she was placed in . . . .‘’ and decided “not to long for their old life. . . .” (Villeneuve, 227 ).” Villeneuve’s final description of Belle mentions that she is beautiful. This is nearly a passing reference, clearly indicating that it is not her physical appearance that gives Belle her beauty, but rather the aforementioned qualities. Another definable characteristic that separates Belle from other fairy tale heroines is that the author emphasizes Belle’s superior intelligence, having received along with her sisters a formal education. She is especially talented in music. Belle uses these skills to adapt to her new circumstances. Because she chooses to be happy, rather than wallow in misery, her sisters feel that she is flawed. The writer points out that this stems from jealousy and that “every intelligent person” sees Belle for who she is and prefers her to the others (Villenueve, 228).” This implies that those who mock her spiritual strengths are quite the opposite. Once Belle is established as having the strength of character to overcome adversity, she begins her journey to romantic love when she asks her father to bring her a rose. In symbolism the rose equates beauty with the pain present in its thorns. Hence the rose foreshadows the trials and sufferings which the characters face. A rose is also connected with passionate love, especially when it is red. Belle’s request to her father unwitting puts in motion her transformation from a young lady who is passionately good, to one who passionately falls in love. True to his promise, her father, having stumbled upon the Beast’s castle to take shelter, picks one rose from the garden. Then the Beast appears to accuse him of stealing and threatens to put him to death. Belle’s father pleads for his life, mentioning his family. The Beast agrees to the father’s safety in exchange for one of his daughters. The only stipulation is that she must come of her own free will. Of what the father and the reader are unaware is that this is a situation set up by the Beast’s very own fairy. The Beast is not being cruel to the father, nor is he inclined to kidnap young ladies. However, he had been cursed by a jealous fairy that was refused by the Beast. In revenge she made him into a monster unable to express his intellect. The only way he could be restored was to have a woman agree to marry him of her free will. The Beast was advised to make this ultimatum on Belle’s father because the good fairy had herself picked Belle as the woman who would be suited to break the curse. Belle does succeed, but not without a great deal of personal and spiritual trials. Upon arriving at the Beast’s castle and finding that she was to be left alone all day, she recognizes that she is in danger of suffering from melancholy. Hence she chooses to stave that off by looking to improve her intelligence and talents. The only time she meets with the Beast is at dinner where the conversation is dull and always ends with an awkward proposal from him. This is disconcerting for Belle because he is so sad, but pity is not enough to compel her to marry a Beast. Every night however, Belle has happy dreams where a handsome prince comes to her and with whom she finds stimulating and intelligent conversation. She begins to fall in love with this dream-prince and always looks forward to bedtime so that she can be with him. As pleasant as their time spent together is, now and then the Prince chastises her for refusing to look beyond what she sees physically. He is pointing out that Belle, though nearly perfect in every way, still has a certain snobbery which prevents her from perceiving the beauty in the Beast’s soul. This is due to the fact that she is focused on his looks and poor intellect. The reader guesses at once that the Prince is the Beast visiting Belle in his true form through the venue of a dream, often the means of spiritual communication in myth. Partly due to interactions with her nighttime lover, Belle becomes more sympathetic and fond of the Beast, gradually seeing the good qualities in him. When the Beast allows Belle to make a visit home, she is late returning and finds the Beast near death. Seeing him in this state, and the thought of losing him, reveals to her that she loves him. She agrees to become his wife, and the Beast abruptly leaves her. Belle, used to this routine, is not concerned and merely retires to bed. Here she dreams that her handsome prince is lying as though dead. She then wakes up to the brightest morning she has ever experienced at the castle and is startled to see her prince lying beside her, albeit on a couch. She realizes that this is the Beast transformed, having gone through death and resurrection in the dream. Because this occurs when they are actually sleeping together, it is revealed in a discreet manner that Belle and her Prince are not only in love, but also passionate lovers. After he wakes up, they marry. It does not take a great amount of imagination to know what happens next. The rose, which began the journey, has completed its purpose. A rose plays a different role in the 1991 cartoon, though it retains its meaning of romantic love. The Beast has a limited time to find someone to love and earn her love, or he can never break the curse. The rose serves as a time-keeper. As each petal falls, the Beast’s hope for true love is depleted. Belle is introduced in the movie as the woman who will save him. However, unlike the Villenueve character, she is not admired for her intelligence by those in her village, but is considered strange and an object of gossip. Because she feels she does not fit in and that nobody understands her, she constantly wishes for more than her “provincial life” and dreams of adventures with somebody to share it. Belle receives a rude awakening from this fantasy when her father is captured by the Beast and she trades her life for his. She reconsiders her dismissive attitude towards her former life explicitly in the expanded stage version. After she is locked up in her room she laments: “What I’d give to return to the life that I knew lately/And to think I complained of that dull provincial town!” Belle has learned that that there are worse fates than living comfortably in the countryside. As Belle begins to have a more mature view of life, the Beast also journeys away from his childish behaviors. He begins a transformation away from his beastly identity as he, through his friendship with Belle, matures and ceases to have temper tantrums whenever he does not get his way. As the two characters open up to each other, they realize that they have a great deal in common and fall in love. Two scenes are particularly endearing and illustrate this. One shows Belle and the Beast having a snowball fight where they clearly are not inhibited in their enjoyment of each other’s company. The other, in the stage and extended version of the movie, is a charming scene in which they read together, showing that the Beast shares her love of books. Following this is the iconic “Beauty and the Beast” number which sweeps the audience along with the main characters into high romance as they dance the night away in the ballroom. When Belle declares her love for the Beast, his curse is broken and he goes through a physical transformation in great beams of light. The Beast, now in his true human form, moves to Belle, and they have a first kiss that is anything but mildly chaste. The last image the movie presents is the happy couple dancing with the fully restored red rose between them, signifying their romantic and passionate love for each other. These internal spiritual journeys are not made by Belle in the Once Upon a Time episode “Skin Deep.” When Belle first appears she is already a mature woman who decides her own destiny. While she is frightened of Rumplestiltskin at first, this evaporates rapidly and she is quickly her playful self with him. If there was a transformation for her, it does not occur onscreen. Rather, the focus is on Rumplestiltskin’s journey as he takes her in, not to break a curse, but to have a housekeeper. Slowly she endears herself to him, and he begins to change, especially when she falls from a ladder into his arms and light floods the room. He blinks, showing that this is something new to him. His acceptance of this new light is explicit since he tells Belle to leave the blinds as they are. The scene is not merely exceptional because it is a moment of transformation for the Beast, but like the Villanueva version, it is full of sexual imagery. As Belle is held by Rumplestiltksin, sweat is visible upon him and she breathes heavily. He drops her as one who has been burned, and he likewise shakes out his hand. Later he formally expresses his feelings when he presents her with a single red rose. This is not just a flattering gift. A single red rose signifies both romantic and carnal love. Because it is Once Upon a Time’s signature style to have an original take on a fairy tale, the struggle in “Skin Deep” has as its center not Belle’s change to see the good behind the Beast-- this she achieves rather easily--but rather the Beast’s battle to see the good inside him. Rumplestiltskin is the one who must learn that beauty is more than “Skin Deep” and that his outward ugliness does not match his inner soul. Belle presents this to him when they kiss. His inability to handle the revelation is shown by his terrifying rage. All of his love for her, and his feelings of betrayal lead to the violence he inflicts on his possessions. He is venting more than anger. His destruction has all the energy of a man in the throes of passionate love. The fact that this results in destroying precious objects also illustrates that he is trying to destroy the rapture within him which nearly succeeded in breaking his curse. When Belle reminds of him of this, he screams at her to “shut the hell up.” He refuses to listen because it would mean that his outward self really did not reflect his inner one. If he acknowledges that he is more than he appears to be, he would not be capable of doing the terrible deeds he commits. When he meets with Belle the following morning, significantly the sun is shining through the windows. Bathed in this light he tells her to go. He is not just rejecting her, but also his transformation. In the season finale, Rumplestiltskin accurately sums up his time with Belle as “a brief flicker of light amidst an ocean of darkness.” These brilliant and moving moments remind the audience and the readers that without transformation, the story of “Beauty and the Beast” would not have enthralled people for hundreds of years. When reading the story, or seeing the cartoon and television show, it is nearly impossible not to be drawn into the characters’ lives and even to reflect on one’s own choices in life. The drama of the transformation is made complete in the Villenueve and cartoon versions, but both Belle and her Beast in Once Upon a Time still have to make their journeys. The former needs to begin hers and the latter must complete his. This is the formula for the drama that will be needed to sustain the “Tale as Old as Time” over the next seasons. Until both change, there will be no completion, and therefore no happy ending. However, all three Belles and Beasts have a single red rose as their signature which proclaims that enduring love is that which mates them through their tribulations, souls, and conjugal destinies. Work Cited

Madame de Villeneuve. “The Story of the Beauty and the Beast.” Four and Twenty Fairy Tales: Selected from those of Perrault and Other Popular Writers. Public Domain. Spinning Gold

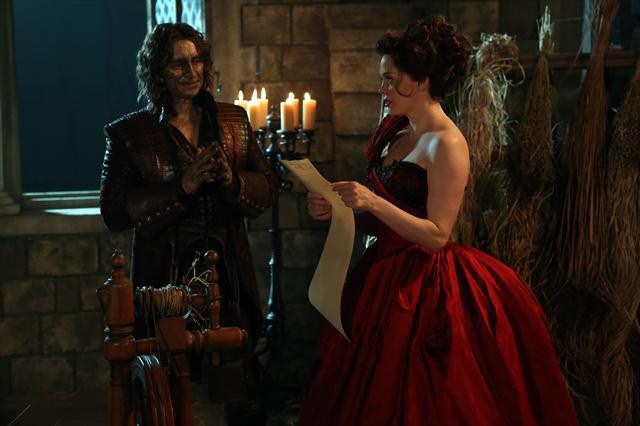

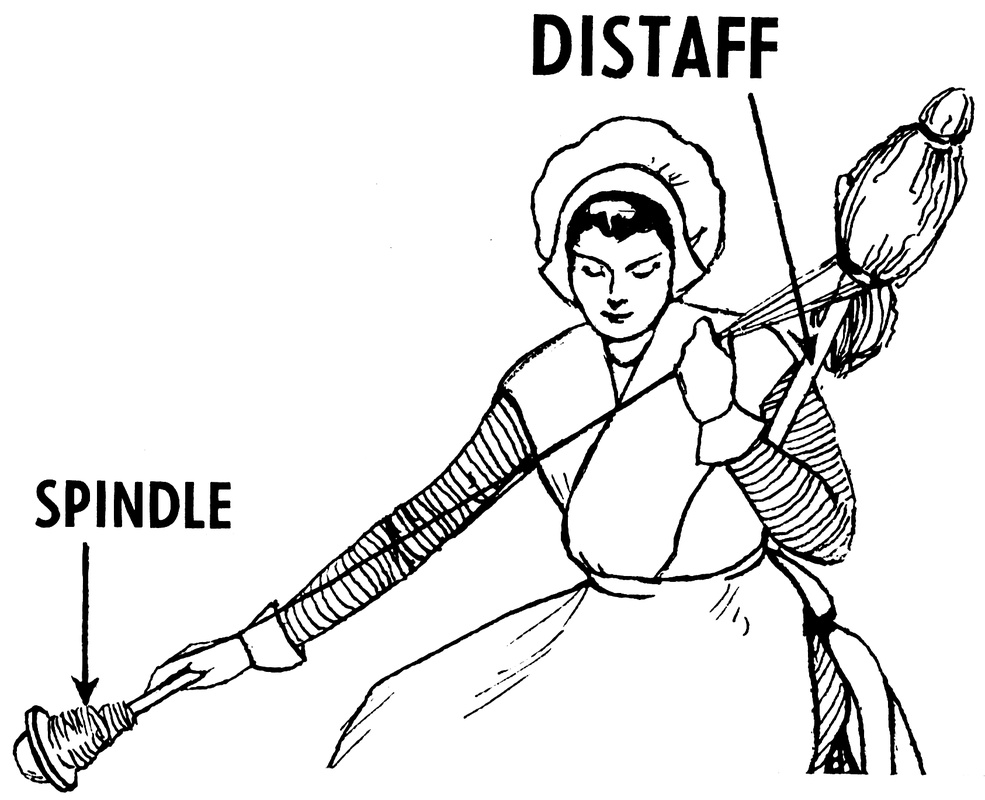

by Teresa Martin --@Teresa__Martin Rumplestiltskin operating his spinning wheel on Once Upon a Time has proven to be an iconic image for the first season of the hit show. But long before ABC premiered its version of this character, the image of a protagonist spinning was repeatedly featured not only in the Grimm’s fairy tale “Rumplestiltskin,” but in innumerous stories collected by the brothers. This art of spinning is difficult and ultimately complex, not only by the mechanization, but by what it represented to society as a means of livelihood practiced by women. Grimm’s Fairy Tales illustrate this history. Moreover, there is an added feature in their tales because spinning is presented with gold as the companion symbol. An examination of these two images can therefore bring a richer understanding of the themes the stories propose, and serve to explain why the one glaring exception to the pattern, Rumpelstiltskin, is so notorious in folklore. One of the images imbedded in the minds of all children who have watched the Disney Classic Sleeping Beauty is that of Aurora pricking her finger on a spinning wheel. However, this image first appeared to readers as a spindle. Archaeological evidence proves that spindles have been used by humans as early as the Stone Age (Castino, 8). By the Eleventh Century the spindle was in common use both in the Eastern and Western world. This simple machine contains two parts: the whorl and the shaft. A whorl is shaped like a drum and serves as a weight at the bottom of the shaft, the long stick-like part ending in a point. The spindle is often used in combination with a distaff which holds the wool or flax. |

OriginsExplore the Arthurian legend surrounding Lancelot, take a trip into the woods to discover the mythology behind Red Riding Hood or learn more about a modern day hero called Snow White. Origins provides unique insights and perspectives from talented writers into the characters we know and love, going far beyond the boundaries of Storybrooke. Archives

August 2016

Categories

All

|