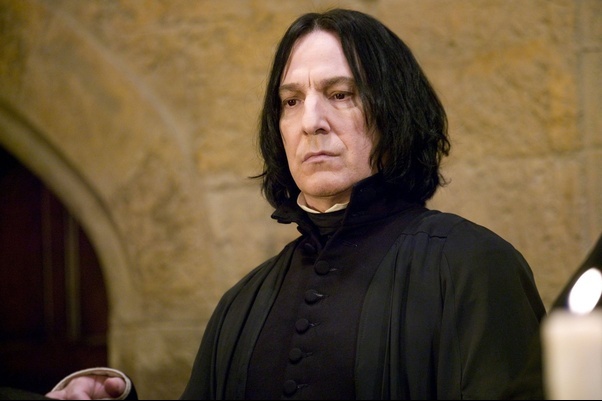

Rumplestiltskin's Transformation in Once Upon a Time: Literary Anti-Hero to Hero Archetype14/1/2014 Rumplestiltskin's Transformation in Once Upon a Time: Literary Anti-Hero to Hero Archetype by Lori J. Fitzgerald (@MedievalLit) and Teresa Martin (@Teresa__Martin) “Ah, but I’m a villain. And villains don’t get happy endings.” ~Rumplestiltskin to his father in Episode 3x11, “Going Home” In the first few episodes of Season One on Once Upon a Time, it was easy to classify the characters into stereotypical roles: Snow White, Prince Charming, and Emma as the heroes/protagonists and the Evil Queen and Rumplestiltskin as the villains/antagonists. However, as the stories unfolded and we learned more during the Enchanted Forest flashbacks, it became apparent that the lines of good and evil were not as clear cut as they were drawn in the original fairy tales or the Disney movie versions. The creators of the show, Adam Horowitz and Eddy Kitsis, emphasized from the very beginning that their take on the characters was not a traditional one; all their creations were complex and dynamic, or changing characters with both virtues and flaws. So the Evil Queen’s revenge stems from the murder of her true love, Rumplestiltskin was betrayed by his wife and lost his son, Snow White casts a curse that kills Regina’s mother and blackens her own heart, and Emma sanctions a Lost Boy’s heart being ripped from his chest to facilitate contacting Henry. These are just some examples of “Fair is foul, and foul is fair,” as the witches in Shakespeare’s Macbeth would chant (I.i.10). So far, none of the major series players in Once Upon a Time are true villains or true heroes. They are all flawed protagonists. Rumplestiltskin in particular is a literary anti-hero, which is a flawed protagonist, or main character, which has qualities usually belonging to a villain, but these traits are tempered with other human, identifiable, and sometimes even noble traits as well. One of the earliest uses of the narrative role of anti-hero is by John Milton in Paradise Lost (1667), who casts Lucifer as the central figure in the first part of his epic poem. Lucifer is overwhelmingly arrogant, powerful, cunning and deceptive, but he is also the most beautiful angel and so charismatic that he is able to rally the other angels in his army after a crushing defeat in the war. During the Romantic period of literature (approximately 1800-1850), the anti-hero was given further “dark” qualities of being emotionally conflicted, brooding, and self-destructive by the poet Lord Byron, and thus the terms anti-hero and Byronic hero became intertwined. A Byronic hero was described by the Romantic literary critic Lord Macaulay (1800-1859) as "a man proud, moody, cynical, with defiance on his brow, and misery in his heart, a scorner of his kind, implacable in revenge, yet capable of deep and strong affection.” Byron’s pirate anti-hero in “The Corsair” (1814) is That man of loneliness and mystery, Scarce seen to smile, and seldom heard to sigh— (I, VIII) And He knew himself a villain—but he deem'd The rest no better than the thing he seem'd; And scorn'd the best as hypocrites who hid Those deeds the bolder spirit plainly did. He knew himself detested, but he knew The hearts that loath'd him, crouch'd and dreaded too. Lone, wild, and strange, he stood alike exempt From all affection and from all contempt: (I, XII) Some well-known Byronic/anti-heroes in literature include the wild and vengeful Heathcliff from Wuthering Heights by Emily Bronte and the secretive, brooding Edward Rochester from Jane Eyre by Charlotte Bronte. Both of these characters may have been patterned after Lord Byron himself, whose own lover characterized him as “mad, bad, and dangerous to know.” Severus Snape in the Harry Potter series is a well-known contemporary Byronic hero, and Anakin Skywalker/Darth Vader can also fit this role. There are several specific character traits of the Byronic/anti-hero that make him the antithesis of the traditional hero, and these traits are as well-tailored to Rumplestiltskin/Gold as his leather outfits and Armani suits. The Byronic/anti-hero has an underlying pathos which shapes his deeds and personality and usually stems from some trauma in his past. Rumple is haunted by his father’s cowardly and dishonest personality and his terrible, blatant abandonment and lack of caring. After striving to escape his father’s reputation, he becomes labeled as the village coward anyways when he hobbles himself to escape the battlefield and return home to be the father he never had. He becomes the Dark One to keep Baelfire by his side and out of the Ogre War, and he creates the Curse to find his son. All of his misdeeds stem from his father issues. The Byronic/anti-hero’s pathos often creates problems with relationships and intimacy. Rumple does not know how to truly please his son after the Dark Curse and tries to buy his love to keep him close. “I am a difficult man to love,” he proclaims in episode 1x12 “Skin Deep,” and his troubles with Belle in the first part of Season Two stem from his inability to bare his secrets and faults to her. The Byronic/anti-hero is also often misunderstood by others. This is the reason Belle, who can see the man within the Beast, is Rumple’s true love, his emotional stabilizer, and moral center, and also why Neal cannot see Rumple’s true, noble intentions towards Henry in Neverland. The Byronic/anti-hero’s motivation is usually self-interest or self-preservation, and Rumplestiltskin certainly has that “nasty habit.” This character also believes that the end justifies the means. Rumple deserts the army and shames his wife in order to be a good father and manipulates and twists Regina into The Evil Queen so that she can enact the terrible curse that will lead him to his son. In Episode 2x01 “Broken,” Belle tells Rumple, “You are still a man who makes wrong choices” after he chooses to give into his angry desire for revenge, and often this character type chooses the wrong path because it is the easier one. However, there is a line that the Byronic/anti-hero will not cross into true villainy. Rumple has torn people’s hearts out, turned them into snails and crushed them beneath his boots, but he refuses to allow the Sherriff of Nottingham to rape Belle in Episode 2x19 “Lacey.” Rumple actually looks astonished at the suggestion of the “trade” and magically rips the Sherriff’s tongue out as an answer. He recognizes that Belle, in the time he has spent with her, is a good, innocent person and will not allow her to be harmed. However, at the end of Season Two, without Belle’s moral grounding but Lacey’s goading instead, Rumple is about to kill Henry on the swing. It is obviously a fine line that he walks between anti-hero and true villainy, but it is the purpose of Belle’s character to keep him as a protagonist, albeit a flawed one. Despite flaws, bad deeds, and sketchy justifications, readers are fascinated by the Byronic anti-hero in literature and actually root for him. And we all know that in the eyes of Dearies, Rumple can do no wrong, even when he does! One last important character trait of the Byronic/anti-hero is that he often seeks revenge and/or redemption. Rumple sends the wraith after Regina in “Broken” and duels Hook for stealing his wife, Milah, in Episode 2x04 “The Crocodile,” and seeks to apologize and make amends to Neal throughout Seasons Two and Three. However, his biggest act of redemption in the series so far is his self-sacrifice in order to save Neal and Belle from Peter Pan in Episode 3x11 “Going Home.” This sacrifice is a narrative upon which myths and legends from time eternal have expounded. Heroes often go on great journeys, even passing through death, to return to the living. Osiris, the god of the underworld in Egyptian lore, after being murdered, was briefly brought back to life in order to impregnate Isiris and bring about a new beginning with the son she bore. Moreover, in the book The Universal Myths, the author cites the Chinese story of King Mu who travels to the empire where death is, only to be returned by the Queen of that empire to the world of the living, having admired his courage for undertaking the quest (Eliot). Also cited is the Epic of Gilgamesh, in which the hero goes to the world of immortals and, though he is not returned, he is allowed to gaze upon its glory. In all of these some sort of transformation or greater good is achieved (Eliot). Such quests fit within Joseph Campbell’s identity of the Hero archetype as “someone who has given his or her life to something bigger than oneself,” one of which is to save others (Campbell). Rumplestiltskin performs this act when he gives up his life to save the ones he loves in “Going Home”. He does so while proclaiming himself a villain, but nothing could be farther from the truth. Rather, in his very act, Rumplestiltskin transforms from an anti-hero to a hero. The special effects confirm this when instead of the purple or black smoke familiar to the audience, bright light shines forth. Such light is associated with resurrection, most commonly associated in western eyes to the figure of Christ. This connection is rather explicit in that not only does Rumplestiltskin’s sacrifice redeem both himself and his dear ones, but the very act of wielding the dagger in this manner changes an instrument of death into the object that makes possible both his redemption and resurrection. Yet while this moment may evoke such images and connections, Rumplestiltskin is far from an allegory of Christ, much like Gandalf, the wizard in The Lord of the Rings. He made a similar sacrifice, killing an evil creature and losing his life in order to save his friends, then came back to life, transformed. Tolkien confirmed that “…though one may be reminded of the Gospels; it is not the same thing at all….” Gandalf died and was “sent back with enhanced power,” but he was not divine (Tolkien). This could be describing Rumple, who will likely have “enhanced power” through a transformation of his curse into good, or even the breaking of the curse. Ultimately though it is Rumplestiltskin’s selfless giving of his life for others that mark him. In The Lord of the Rings, Gandalf’s reappearance occurred in a forest. It will be interesting to see if Rumplestiltskin returns in The Enchanted Forest. Undoubtedly though, the moment will be one that Tolkien described as “euchastrophe” which, appropriately for Once, is found in a fairy tale: In its fairy-tale—or otherworld—setting, it [euchastrophe] is a sudden and miraculous grace: never to be counted on to recur. It does not deny the existence of eucatastrophe, of sorrow and failure: the possibility of these is necessary to the joy of deliverance; it denies (in the face of much evidence, if you will) universal final defeat and in so far is evangelium, giving a fleeting glimpse of Joy, Joy beyond the walls of the world, poignant as grief. It is the mark of a good fairy-story, of the higher or more complete kind, that however wild its events, however fantastic or terrible the adventures, it can give to child or man that hears it, when the “turn” comes, a catch of the breath, a beat and lifting of the heart, near to (or indeed accompanied by) tears, as keen as that given by any form of literary art, and having a peculiar quality. In placing this eucatastrophe into Rumplestiltskin’s story, the writers have hence created their own fairy tale within the great fairy tales they use as resources. The anti-hero is now a hero, whether he wishes it or not. Once Upon a Time is a show in part about journeys of self-discovery with dynamic characters that are constantly changing and evolving, like the flawed protagonist Rumplestiltskin. As an anti-hero, he is dark, conflicted, and misunderstood, yet there is still good in him, as seen by both Belle and the audience, and therefore hope for redemption. When Rumple sacrifices himself to stop Pan and save Belle and Neal from torturous deaths, he further changes by entering the realm of the Hero archetype. In facing his enemy without magic, he finds the courage within himself that has always been there and saves not only his loved ones but all the residents of Storybrooke. By placing Tolkien’s "Eucatastrophe" into Rumplestiltskin’s story, the writers have once again added a unique narrative to the familiar fairy tales and this anti-hero becoming the Hero archetype may be one of the journeys that eventually leads Once Upon a Time to its “happily ever after." Works Cited Campbell, Joseph, and Bill D. Moyers. The Power of Myth. New York: Doubleday, 1988. 231. Print. Eliot, Alexander, Joseph Campbell, and Mircea Eliade. The Universal Myths: Heroes, Gods, Tricksters, and Others. New York: New American Library, 1990. 232-235. Print. Tolkien, J. R. R., Humphrey Carpenter, and Christopher Tolkien. "Letter 151." The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1981. N. pag. Print. Tolkien, J.R.R. "On Fairy Tales." N.p., n.d. http://public.callutheran.edu/~brint/Arts/Tolkien.pdf - Web.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

OriginsExplore the Arthurian legend surrounding Lancelot, take a trip into the woods to discover the mythology behind Red Riding Hood or learn more about a modern day hero called Snow White. Origins provides unique insights and perspectives from talented writers into the characters we know and love, going far beyond the boundaries of Storybrooke. Archives

August 2016

Categories

All

|