|

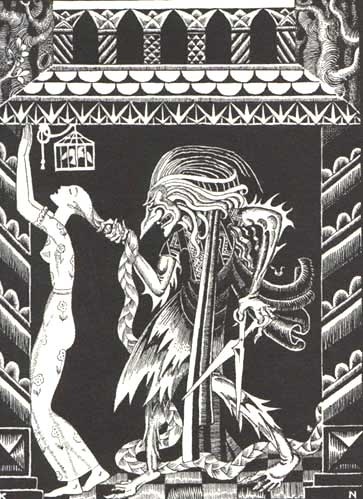

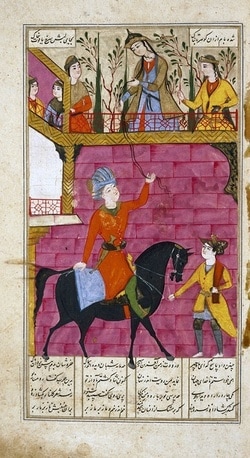

Seeking Rapunzel by Chris Fitzner (@chrisfitzner) “Rapunzel” is a deceptively simple tale; even the name of the title character is obviously German, which would make sense seeing as it was first introduced to the world at large by the Brothers Grimm. But as I dug into the soil and began to pull at the roots of the story, I found that they ran much deeper than I had suspected. It is a story with which most of us are familiar. A husband, desperate to appease his ailing wife, gets caught stealing the lettuce she craves so desperately. The price for the theft is their long awaited child and the witch whisks the baby girl away, eventually shutting her in a tower that has neither a door nor stairs, to keep her safe from the world. Rapunzel grows up beautiful, with golden hair the witch climbs up in order to visit the tower. But the witch cannot keep the world out forever; eventually a prince discovers Rapunzel, drawn by her enchanting singing. He figures out the trick to gaining access to the tower and begins visiting after the witch is gone and the two fall in love. The witch discovers them and banishes Rapunzel far away to fend for herself and springs a trap for the prince, who falls from the tower and blinds himself on the brambles. After a time of wandering, Rapunzel and the prince are reunited, her loving tears restoring his sight. Happily ever after, right? This story makes me think twice about crossing an old crone at the salad bar. The tale that we know as “Rapunzel” came to us from the Children’s and Household Tales collection, first published by the Grimm brothers in 1812. Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm collected oral folk tales and wrote them down, sometimes editing them over time and removing the more cruel or sexual elements in some of the stories. However, their “Rapunzel” bears a strong resemblance to a French story titled “Persinette”, written by an aristocrat, Charlotte-Rose de Caumont de la Force and published in 1698. This version with its title character, Persinette (parsley), is almost identical to the Grimm’s version save for having a more detailed ending with Persinette and her lover suffering even more than Rapunzel and the prince before their eventual reunion. But if “Rapunzel” was French, how did Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm come across it as an oral folktale? They have J.C. F. Schulz to thank for that, as his translation of “Persinette” is thought to be the indirect source of “Rapunzel”. Schulz also changed the heroine’s name to Rapunzel. The Grimm brothers, however, were unaware of the stories of Schulz and Madame de la Force and assumed that the story was oral in its origin. Several similarities to Schulz’s translation may imply that at least one of the Grimm’s human sources had heard the Schulz telling. The intermixing of cultures and versions were common with folktales and took place frequently until the printed versions of the Grimm Brothers and Perrault were introduced. The trail doesn’t quite end (or begin, rather) in France with Madame de la Force either. The first literary traces of “Rapunzel” can be found in 1637, in Giambattista Basile’s Pentamerone in the story “Petrosinella” (which, derived from petrosine, again, means parsley). In Basile’s version, the lovers elope rather than suffer at the witch’s hands before a reunion. It may be that the ending we know best could have been simply the artistic licence of Madame de la Force and a craving for tragedy on the part of her readership. Flavours of the later “Rapunzel” do seem to carry Mediterranean undertones, though the name of the heroine may change from tradition to tradition. In some cultures, the witches are cannibalistic. The original folktales often involved the heroine and the prince fleeing the tower rather than succumb to the punishment that would result upon discovery. In these variants, the witches pursue the lovers but are outwitted three times (the girl often using magic that the witch taught her, no less). On the third obstacle, the witches in these tales are rendered harmless or killed, and the lovers are free. The two most memorable components in “Rapunzel”, for me at least, are the tower and the heroine’s long hair. In the versions that I have come across in my life, the witch locks Rapunzel away around age twelve to keep her safe from the world which seems to say that as the elder, she obviously knows what’s best and her child does not. The “maiden in the tower” trope can be found littered throughout old stories and “Rapunzel” holds similarities to the Tenth Century Persian tale of Rudaba, in the epic poem Shahnameh by Ferdawsi (circa 1010 CE); in it, Rudaba offers to let down her hair so that her lover, Zal, may climb up to her. We also find the tower trope in Saint Barbara, who lived sometime in the Mid-Third Century. Saint Barbara’s father locked her in a tower to preserve her from the world. During her imprisonment, she converts to Christianity from the pagan beliefs of her birth. The message of the tower and its representation of tradition, authority, and power rings loud and clear. As Mother Gothel sang in Tangled: Mother knows best. Tangled is perhaps the best known adaptation of “Rapunzel” at present and my favourite to date. It is a very loose adaptation from the Grimm’s telling to be sure. Plucky Rapunzel leaves the tower against her “mother’s” wishes in order to achieve her dream of seeing the lights, armed with only an iron skillet, a mile of magical hair, and her incredibly positive attitude. Compared to the rather flat character in the folklore, this plucky princess seems like a huge departure, or is it? The plucky lovers escaping from the witch in the Mediterranean tales seem more on level with Disney’s princess than the Grimm’s, even with all of the liberties the Disney company took with the story.  Charming (Josh Dallas) and Rapunzel (Alexandra Metz). ABC, 2014 Charming (Josh Dallas) and Rapunzel (Alexandra Metz). ABC, 2014 Once Upon a Time’s very own is slated to appear in Episode Fourteen, “The Tower”. Portrayed by Alexandra Metz, Once has already broken any and all pre-established notions of how this character should look. Will they spin straw into gold with her character as well? Will we have a new member in their ranks of plucky princesses or will she be doomed to be another footnote in the greater story arc? We will have to wait and see.

0 Comments

By Chris Fitzner - @ChrisFitzner

Alone in the stairwell and hidden from the view of my relatives, I gazed, wide eyed, at the beautiful antique mirror hanging on the wall of the landing. What was it like on the other side of the mirror? Could the reflection be its own world, simply an inverse of the world I lived in and if so, how could I get into it? I would poke at the hard glass surface, waiting for that magic moment when the barrier fell and the glass was suddenly pliable and I would step through into the heroic adventure I read about and longed for. By Chris Fitzner

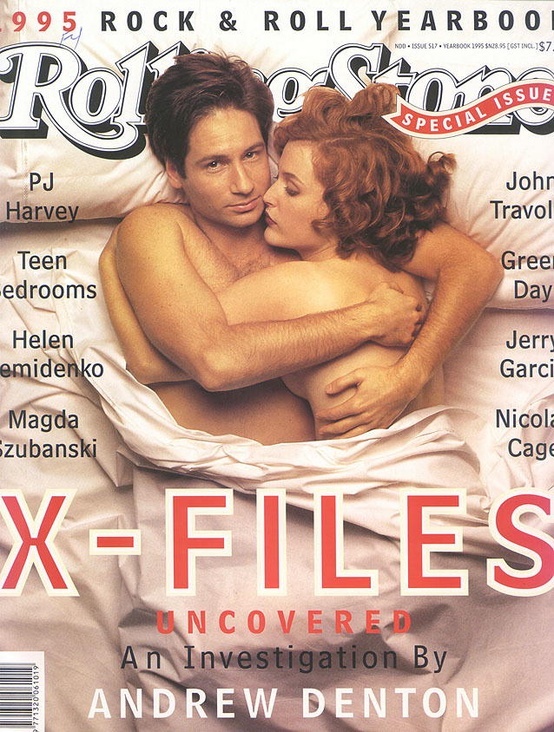

These days, what is a fandom without at least one ship? In Once Upon A Time many of us are familiar with the terms Snowing, Swan Queen and Rumbelle. But where did 'shipping' begin and for that matter, what the heck is a ship? For those of you envisioning a multi-sailed tall ship bobbing in a beautiful blue harbour, I hate to break it to you but that is not the droid you are looking for. According to Wikipedia, so you know it must be true, in fandom, 'ship' is a word derived from 'relationship' and the belief that two characters, real or not, will be in a romantic relationship. In recent pop culture, Twilight comes to mind with the rabid fans on both Teams Edward and Jacob. It became mainstream enough for official merchandise and features in entertainment news. But that's not where it started. The act of 'shipping' pre-dates the term and is thought to have begun in the 1990s with the television hit The X-files. The ship of agents Scully and Mulder was as hot as anything I could compare it to now. Rolling Stone magazine capped it off, in my mind, in 1995 with the couple featured on the cover, lying in each other's embrace with only the bed linens for company. Above: The Little Mermaid: Dissolving into Foam, Edmund Dulac, 1911 By Chris Fitzner Glorious red hair, green tail, an amazing singing voice; when you say ‘mermaid’ that is the mental image the average person would draw. When Disney’s Ariel makes her splash debut in season three of Once Upon A Time, there’s a good chance that will be what she looks like. But Ariel is only the tip of the iceberg as far as mermaids go. Mermaids have been a part of folklore traditions throughout the world for thousands of years. “Mermaid” is a compound of the Old English mere (sea) and maid (girl or young woman). The Old English equivalent being merewif. But the first stories of mermaids (or mere type creatures) make their appearance in ancient Assyria circa 1000 B.C.E. in the form of the goddess, Atargatis, who loved a human shepherd and after accidentally killing him, Atargatis leaped into the water in shame, transforming herself into a fish. The water was unable to hide her divine beauty and she took the form of a mermaid, human above the waist and a fish below the waist (similar to the Babylonian god, Ea). The ancient Greeks recognized Atargatis under the name Derketo. Though mermaids have long been associated with music, their voices having the ability to enthrall and lure sailors to their deaths, Andersen’s tale contains no singing crabs, annoying sea gulls or cowardly flounders. I certainly can’t blame the Walt Disney Company for wanting to jazz it up a bit; or a lot. In mermaid fandom, ‘mermaiding’ has grown in popularity alongside fantasy cosplay. Mermaiding is the practice of performing dolphin kicks and other movements underwater while bound in a costume mermaid tail. Mermaid performances, most famously done by the Weeki Wachee Springs Mermaid Show in Florida, began as roadside attractions and reached the height of their popularity in the mid-twentieth century. In Halifax, Nova Scotia, you can even hire a mermaid for your event. Raina the Halifax Mermaid entertains and educates on local ocean ecology issues. (http://rainamermaid.blogspot.ca/) The most famous story and the origins (if you will) to Ariel is “The Little Mermaid” by Hans Christian Andersen, published in 1837. It has always struck me as a sad tale, especially after the happier Disney version, as the little mermaid doesn’t get her happily ever after with the prince and even her life on land was a torment. Your tail will then disappear, and shrink up into what mankind calls legs, and you will feel great pain, as if a sword were passing through you. But all who see you will say that you are the prettiest little human being they ever saw. You will still have the same floating gracefulness of movement, and no dancer will ever tread so lightly; but at every step you take it will feel as if you were treading upon sharp knives, and that the blood must flow. “The Little Mermaid”, Hans Christian Andersen In the end, her beloved prince marries another and in order to return to her sisters in the sea, the mermaid must stab the prince through the heart. In the end, the little mermaid cannot kill the prince, for love of him and his bride and she flings herself overboard, appearing to become sea foam and turning into a daughter of the air. Mermaids do not have immortal souls and can only obtain one by marrying a human; by becoming a daughter of the air, the little mermaid could earn her way to a soul after three centuries. From ancient myth and folklore, mermaids have glided through the centuries, most often as unlucky omens, foretelling disaster and provoking it. Though they could occasionally be beneficent and benevolent, they were often dreaded signs to sailors and those in coastal cities. Sailors reported seeing mermaids, sometimes swimming alongside their vessels. In January 1493, Christopher Columbus reported seeing three mermaids swimming ahead of his ship off the coast of present day Dominican Republic. Traditionally depicted as beautiful with long flowing hair, Columbus said they weren’t half as beautiful as they were painted. In this case as with the others, it is believed that it was misidentification. Mermaid sightings (when not made up) were likely manatees, dugongs or Steller’s sea cows (extinct in the 1760s). Manatees and dugongs belong to the order Sirenia; fully aquatic, herbivorous mammals that inhabit rivers, estuaries, coastal marine waters and swamps. They look clumsy but are fusiform, hydrodynamic and highly muscular. They were often taken for mermaids and if I were at sea for as long as mariners before the twentieth century, anything might seem attractive after a while! Sadly, for those of us longing for real mermaids and despite sightings even in the twentieth and twenty first centuries, the U.S. National Ocean Service stated in 2012 that no evidence of mermaids has ever been found. That doesn’t stop the wild and fertile human imagination though and mermaids are firmly entrenched in it. From Melusine in Western Europe, rusalkas in Eastern Europe (though the rusalkas lacked a fish-like tail), mermaids and their water spirit counterparts haunt the waters of our past and present pop culture. With Ariel scant months away from our television screens, the directions that the writers of Once could go are as endless as the deep blue sea. Might we see an Ariel with some of the darker, more mischievous traits of old folklore or will she be more the bubbly red head of our childhood memories? We’ll have to wait until season three airs to find out.

By Chris Fitzner

More than two thousand years have passed since the time of the ancient Greeks, but their rich body of myths remains with us, resonating through the centuries. Many of us grew up learning the most basic Greek myths and about the twelve Olympians: Zeus, Hera, Athena and Apollo among them, still familiar “household names”; deities, heroes and impossible beasts. The Greeks lived in a harsh and often inexplicable world and as human beings do, they turned to religion to explain the whys and hows of that world. Why was there thunder and lightning in the sky? Oh, Zeus must be angry. How did the sun cross from east to west each day? Apollo rode his fiery chariot across the sky. In our own century, we have science to explain much of what the ancient Greeks attributed to their gods (seasons, disasters, celestial events, wars). The technology in everyday life and medical advancements would seem nothing short of miraculous to an ancient Greek. We don’t need the old stories to cushion our lives anymore, but the ancient Greeks are still with us, in our language and culture, in ways we probably don’t realize. A few years ago, a younger girlfriend of mine lamented her newly acquired single status. She had been having a bad time in the relationship department and turned to me for comfort. Having said some of the usual post-relationship phrases and telling her that she was a strong, lovely woman and didn’t need a man to be happy, I discovered that by being married myself, none of my encouragement mattered to her. “It’s easy for you to say” is something I hear a lot when giving what I feel to be honest advice. To my friend and many other young women, finding The One, their own handsome prince, and getting married is one thing they want above all. I don’t have a problem with their hopes and dreams, but all of them couldn’t really explain why they had them except with a “that’s just what you’re supposed to do.” I’d like to set down right now that I have no problem with homemakers, stay-at-home-moms, or housewives; I’ve been a housewife too and I have an ocean of respect for these women. My irritation begins when it’s done because that’s what is expected because you are a woman, it’s your role. Fulfillment can and does happen without a ring on your finger and a baby in your arms.

|

OriginsExplore the Arthurian legend surrounding Lancelot, take a trip into the woods to discover the mythology behind Red Riding Hood or learn more about a modern day hero called Snow White. Origins provides unique insights and perspectives from talented writers into the characters we know and love, going far beyond the boundaries of Storybrooke. Archives

August 2016

Categories

All

|